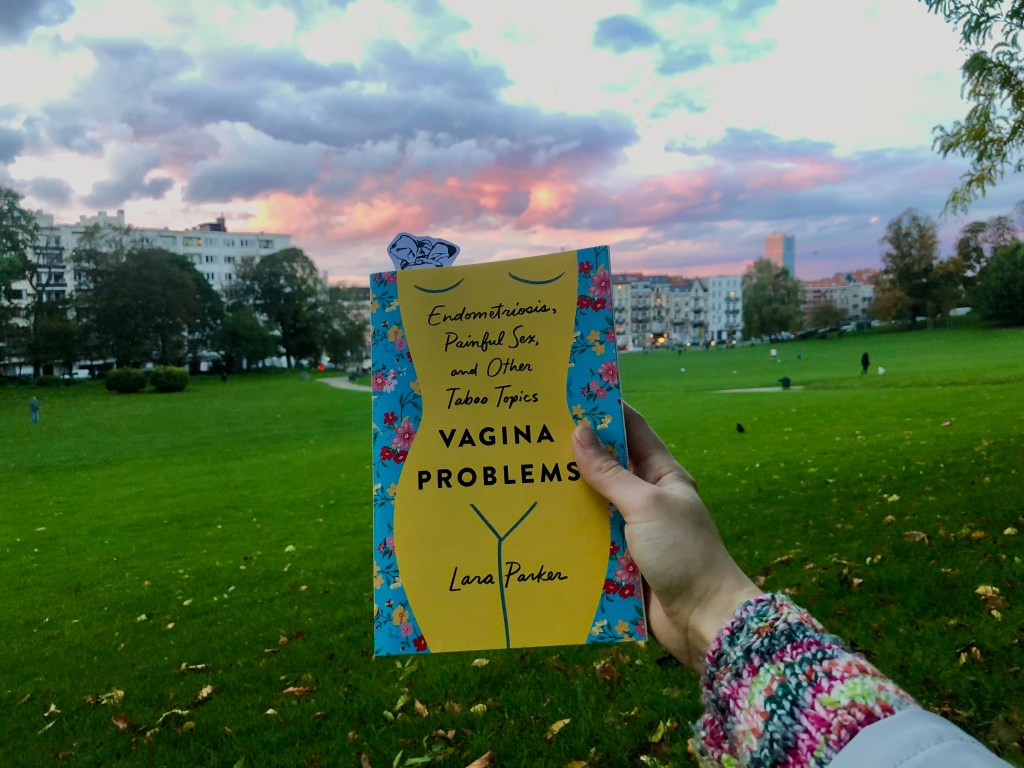

Much like with Lara Parker’s Vagina Problems, I don’t think it’s entirely appropriate for me to ‘review’ Fran Bushe’s My Broken Vagina because the content is so close to home. I’ve also seen Bushe’s one-woman show Ad Libido three times, discussed it several times on this blog and written about it during the same module of my MSc that I discussed in my last blog. I’m a big fan and completely biased, so instead of reviewing My Broken Vagina, here are some thoughts I had while reading it.

My Broken Vagina is a frank, funny and warm book where Bushe describes her experience of feeling like her vagina is broken and her quest to fix it: spoiler alert, the only thing that’s broken is sex education. As soon as I started reading My Broken Vagina I felt like I was being hugged by Ad Libido. Each of my three viewings of Bushe’s show marked significant chapters in my own relationship with my broken bits but having its wisdom captured in a written form that I can return to and share beyond the limits of the theatre feels very special. Just like her play, Bushe’s book is laugh-out-loud funny, genuinely educational and wonderfully moving. As an added bonus, it’s filled with amazing, poster-worthy illustrations.

Among many important points that come up in My Broken Vagina, is one that I am always particularly fascinated by: ‘the conversation’. That is, the great pleasure of telling a potential new intimate partner that they might need to change their expectations of sex because of sexual pain. Perhaps it sounds simple but it’s been something of a minefield for me for many years and I was thrilled to find it in Vagina Problems and now My Broken Vagina too. It’s refreshing to see it being discussed openly because advice about talking to a partner about sexual pain nearly always assumes you’re in an established, monogamous and heterosexual relationship. It’s likely I relate to Bushe and Parker’s musings on the subject so much because we’re all discussing experiences of being single with sexual pain as white, cis women dating men, but there are definitely similar threads running through discussions of ‘the conversation’ that I think are worth talking about. Take a look at these quotes from My Broken Vagina and Vagina Problems:

‘Yeah, haha, and by the way, I might never be able to have sex with you. But I’m still pretty funny and I can make decent banana bread.’

Lara Parker, Vagina Problems – 114

‘At what point on a date with someone new, do you say, “Hey, I know we are probably going to go back to mine and bang it out/make sexy magic, but I want you to know … I might find this very painful”.’

Fran Bushe, My Broken Vagina – p.36

Recently, I got over my fear of ‘the conversation,’ by coming to the remarkable discovery that it doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter for two reasons. First of all, it is a complete distraction from the actual important bits of getting to know someone and figuring out if you even want to get intimate with them:

‘I nodded when I was supposed to and laughed on cue, all while thinking about what it might be like to tell him that I might not ever be able to have penetrative sex with him.’

Lara Parker, Vagina Problems – p.115

‘The fear of having this conversation with a stranger not only meant I had never had a one-night stand, it also meant I’d stay in bad relationships longer than I should.’

Fran Bushe, My Broken Vagina – p.37

Secondly, it doesn’t matter because no matter how you present the information, you cannot control the other person’s reaction. Nothing has ever been more out of your control and, if I’m totally honest, a person’s reaction to that revelation can often be a good test of character. The last time I told someone I was dating that sex might not be what they were expecting or used to but that it could still be fun and good if they kept an open mind, the guy in question went quiet for a moment and became very focussed on the beer bottle in his hand. I was about to panic babble when he suddenly became very animated and asked me why his ex-girlfriend had instructed him to stuff a head of garlic up her vagina to prevent UTIs. It cued internal howls of laughter and shook out all the anxiety I had about ‘the conversation.’ Shock therapy? There is no way I could have anticipated that response (nor any way I could have answered his question.)

This subject and many others are built upon in much funnier ways in Bushe’s writing. Bushe’s play came to me (steady on) by chance when I was still feeling very much alone in my experience of sexual pain. The Gilmore Girls gif I used to describe how Ad Libido made me feel the first time I saw it is still better than any words I’ve found to describe that feeling. The idea that some scared teenager discovering their body might find My Broken Vagina before sifting through the heaps of unhelpful and incorrect information and advice Bushe and others like myself have had to sift through warms my soul. I wonder how my former Catholic all-girls school would feel about a sudden library donation? I think I’ll find out, because at the heart of My Broken Vagina is a lesson we can all do with reminding of from time to time: that there’s a big difference between feeling broken and being broken.

You can buy My Broken Vagina from all good bookshops now and until 19 June you can stream Ad Libido online here – I think I’ll be getting my fourth viewing in! P.S. Speaking of vaginas, if you’re in London get to the Vagina Museum for what looks to be an amazing exhibition, ‘Periods: A Brief History,’ featuring the amazing Hazel Mead. Wish I could get there!