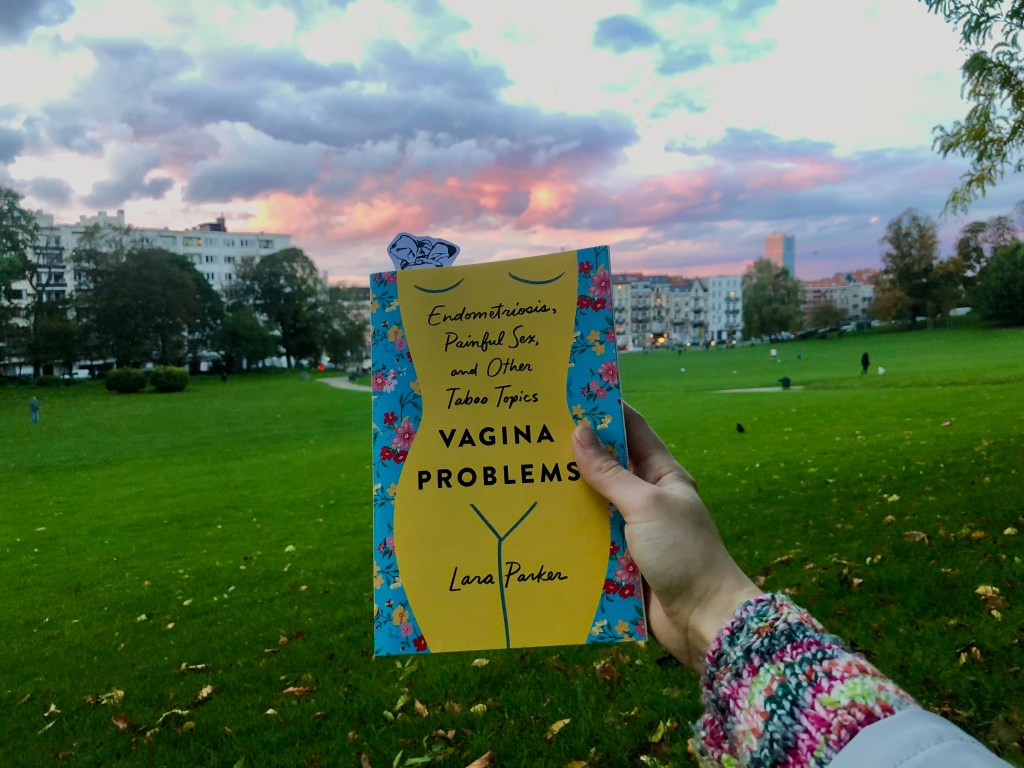

I love non-fiction – so much so that this blog is probably poorly named. Yet the book I’m going to write about in this blog was pretty difficult to read. It had nothing to do with the writing and a lot to do with the fact that it crossed the line from reading non-fiction to broaden my worldview to reading about my own reality. So while this is a blog about reading Lara Parker’s Vagina Problems: Endometriosis, painful sex and other taboo topics, it is not a review – the subject matter is far too close to home for me to be able to give an ounce of objectivity.

Vagina Problems was difficult to read because it made me think about things that I spent the best part of the last year trying not to think about. I’m not sure if it’s the Mirena coil or a perk of COVID-19 restrictions, but my symptoms have become increasingly unpredictable leading to multiple weeks of relative relief that I affectionately call ‘hormone holidays’. These weeks are by no means pain free but the pain is manageable, I can hike and concentrate and think about something other than pain. During these weeks, I again start to wonder if I no longer need to seek treatment for endometriosis, maybe it wasn’t ever that bad in the first place, maybe further intervention isn’t necessary. But Vagina Problems reminded me how much I continue to adapt my life around my own vagina problems. And how while it’s hard to remember pain after the fact, the moment it returns, it is totally life-disrupting. Every time I learn about an external factor that worsens my pain, like sex, running and now stress, I’ve been in the habit of removing that thing from my life. Unfortunately, removing stress isn’t an option and I’m sick of stripping away the good triggers. While I have come to terms with the fact that there probably isn’t a long-term solution to be found at present, it is still worth pursuing one, especially while I have the energy during these ‘holidays’.

“Hearing that voice inside my head that says, ‘You probably wouldn’t be in pain if you didn’t eat that cookie,’ and telling it to shut the fuck up. Because the truth is, I’d still be in pain. But I’d be in pain without experiencing the pleasure of eating a cookie. And that’s not the kind of life I want to have.”

Lara Parker, Vagina Problems – p. 40

Sometimes when I talk about the last year in Brussels, I frame the story as though endometriosis, vaginismus and pelvic floor dysfunction were the last of my worries, with Brexit, chickenpox and a sodding pandemic trumping the chronic problems. But as I anticipate moving house and watch a new housemate as she discovers the city, I realise that my pain is embedded in my experience of Brussels, my work and my house. “This is where I work,” I said as the metro pulled into the platform, “and that’s where I fainted a year ago… and that’s where I vomited once I came round.” Asked why I fainted, I shrugged and said “pain”. Every time I use my work toilets, I’m reminded of how many times I’ve been sick in them, how it’s one of the first places I experienced rectal bleeding, how often I found blood in that small room and was never entirely sure where it was coming from or why. And then there’s the house. That’s where I sat every Friday evening when I came home from work ill, just in time for the weekend. We used to laugh at it, that I was always unwell the moment the weekend started. It took a lockdown for me to piece together that my body starts to send me red flags to rest on Thursdays and that when I ignore them, something breaks the moment I relax. If this has been the good year for my symptoms, then maybe my gauge for goodness is a bit out of kilter.

“I start downplaying what’s going on, or backtracking on what I was trying to reveal … I feel the need to make others comfortable with a situation that I’m definitely not comfortable with.”

Lara Parker, Vagina Problems – p. 131

Also etched on this house are my failed attempts at dating again for the first time since my first laparoscopy several years ago. You can take Parker’s chapter on dating with endometriosis (titled ‘Hi, my vagina hurts, wanna date?’) and just staple it to my forehead so that people can read my thoughts. Perhaps it’s because we’re both white and date men, but it seems as though I’ve been on a very similar journey to Parker regarding pain, sex and communication. Like me, Parker’s pain during sex is not just limited to penetration or insertion, “just getting aroused can cause a shooting pain from my pelvic area throughout my entire body… it’s not exactly an aphrodisiac,” and like Parker, I’ve spent years fretting over when is a good time to break that news to a potential partner. I recently came to the same sucky conclusion as her: “I don’t think there’s ever going to feel like the right time because it will always feel like boiling-hot water burning your tongue after you spit it out”. And when that communication breaks down, or just doesn’t happen, sometimes it backfires and the other person comes across very, very badly. I’ve tried explaining this to friends and never found the words, but now I have Parker’s:

“Maybe he was scared! Maybe I wasn’t communicating what the fuck was happening and not providing an opening for a conversation about it. He was confused, I am sure. And for that, I give him 12 percent of my sympathy. Because guess what? As confused as he might have been, so was I. And I was the one dealing with the actual fucking pain.”

Lara Parker, Vagina Problems – p. 119

When I think about my future in terms of treatment and any potential coupledom, I’m surprised to find them interlinked, after fighting against doctors’ assumptions of such a link for years. But they’re not linked in the way people always assumed. Let’s say I see this top doctor in Belgium and she is as skilled as the world says she is and she greatly improves my symptoms to the point that I can once again have an active and social personal life and have or even enjoy penetrative sex again? What if I entered a relationship after that point and my partner didn’t know what it took to get there – what if there even came a point where it was taken for granted because they didn’t know what a huge deal it was for me? Then on the other side, what if I see this doctor, and like the others that came before her, she can’t do anything for me? It’s hard to imagine having a functional relationship with someone who didn’t witness that process and know first hand that I didn’t chose the result. Although maybe that attitude is rooted in living in a world where women are rarely believed on testimony alone.

I am certain that these aren’t good reasons to start a relationship, and they’re definitely not reasons to have more surgery, yet one intense weekend reading Vagina Problems had me actively using a dating app and on a waiting list for a new gynaecologist after months of dithering on both. I’m still not sure if either of those things are good but somewhere in there, there’s hope.

You can follow Lara Parker on Instagram and buy her book here. At the moment she’s raising awareness about U.S. endometriosis experts who have donated to Trump’s campaign. I join her in saying that they cannot advocate for people with endometriosis when they are supporting racist and sexist policymaking. Doing so is to work directly against the patients they claim to care for. I encourage my U.S. readers (that’s 37% of you!) to cast your vote if you haven’t already and to know that a vote for Trump is a vote against pretty much everything good in this world, including access to safe healthcare. Elsewhere, the all party parliamentary group (APPG) report on Endometriosis has just been published – read it here.